The Awakening Of The Harlem Renaissance

The Renaissance began in the late 1910s with plays featuring black actors rejecting stereotypes and conveying emotions. Poems such as “If We Must Die” introduced a politically defiant protest to the racism and lynching taking place. Soon, there were various political and arts newspapers published by black Americans in Harlem. Religion, especially Christianity became a topic of debate. Opponents of religion believed Christianity was not an answer since discrimination and segregation were most practiced by Christians and in churches. Many African American Christians pushed for more all-encompassing doctrine. Pockets of Islam, Judaism, and Traditional African Religions also found their way into Harlem. Harlem Stride, a new way of playing the piano was invented during this period. At the time, jazz was very competitive with talented musicians. It soon spread quickly through the entire country. Black musical styles attracted more whites who exploited the melodious tenderizes and themes of black composers.

Harlem Renaissance created distinctive African-American identity and artwork

Countee Cullen and Langston Hughes – encouraged blacks to be take pride in their color and unique abilities. Those artists believed that it was only through self-confidence in one’s that the black race would emerge out of their political and economic bondage. Appeals were made to blacks to seek the “folk-way” of doing things.

In poetry for example, Claude McKay’s Harlem Shadows (1922) was well received by an African American populace that was hungry for knowledge and growth. The Black Pride, as it was called, manifested itself in critically acclaimed scholarly and literature works such as Jean Tomer’s 1923 Cane and James Weldon Johnson’s The Autobiography of An Ex-Colored Man (1922).

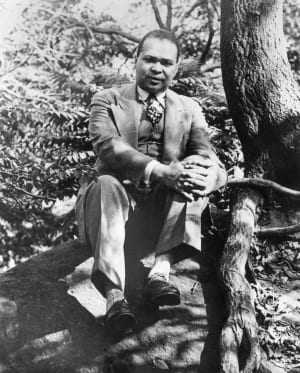

Countee Cullen

Countee Cullen

Countee Cullen had a vibrant life after becoming the adopted son of Reverend Frederick A. Cullen, the pastor of Harlem’s largest congregation when he was 15.

The poet was quickly influenced by the bedrock of talent around him and had already appeared in national magazines before he graduated from New York University in 1925. He published his first book of poems, Color, that same year. His poems explored modern racial injustice at the time using the classical structures associated with white poets.

Tight with a circle of celebrated writers, Cullen became the assistant editor of Opportunity magazine, an academic journal published by the National Urban League.

Cullen later etched his name into Black high society when he married Yolanda Du Bois in 1928, the daughter of civil rights leader W.E.B. Du Bois.

Zora Neale Hurston

Zora Neale Hurston

An author, playwright and filmmaker, Zora Neale Hurston celebrated the culture of the Black rural South like few others. Her love of the South came from her own childhood growing up in the Orlando suburb or Eatonville, the first all-Black town in the country where she was never treated differently or inferior.

Though Hurston’s idyllic upbringing came to an end when she turned 13 and her beloved mother died, the writer continued impressing people everywhere she went and eventually made her way north to Harlem, becoming a friend of Hughes.

The two collaborated on a play together, published posthumously, and Hurston gained recognition for her novels and investigations of voodoo culture.

She died in 1960 at 69, with her latest book, written in 1931, finally published in 2018. Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo” tells the story of Cudjo Lewis, who was believed to be the last survivor of the final slave ship that brought Africans to America.

Louis Armstrong

Louis Armstrong

Known as one of the founding fathers of jazz, Louis Armstrong revolutionized the genre with the work that came out of the Harlem Renaissance.

Growing up in New Orleans, Armstrong was constantly exposed to some of the best jazz musicians in the country. Though his daily life was hard as his single mother struggled to raise him, and he ended up in an orphanage, his love of music and natural talent propelled him to the ranks of some of America’s most famous musicians.

After he moved to New York City in 1924 to join the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra, Armstrong’s unique, soulful and lively solos changed the course of jazz to focus on individual musicians experimenting with sound.

His small group recordings from 1925 to 1928, all during the Renaissance, made Armstrong the most influential musician in jazz, and his singing brought his work to world-wide stardom. Armstrong would later be responsible for enduring hits like “What A Wonderful World” and “Hello Dolly.”

Кем были женщины?

Большинство известных деятелей Гарлемского Возрождения были мужчинами: W.E.B. Дюбуа, Каунти Каллен и Лэнгстон Хьюз — имена, известные сегодня самым серьезным изучающим американскую историю и литературу. И поскольку многие возможности, которые открылись для чернокожих мужчин, также открылись для женщин всех рас, афроамериканские женщины тоже начали «мечтать о цвете» — требовать, чтобы их взгляд на условия жизни человека был частью коллективной мечты.

Джесси Фосет не только редактировала литературный раздел «Кризиса», но также организовывала вечерние встречи для видных чернокожих интеллектуалов Гарлема: художников, мыслителей, писателей. Этель Рэй Нэнс и ее соседка по комнате Регина Андерсон также проводили собрания в своем доме в Нью-Йорке. Дороти Петерсон, учительница, использовала бруклинский дом своего отца для литературных салонов. В Вашингтоне, округ Колумбия, штат Джорджия, «вольные беспорядки» Дугласа Джонсона были субботними ночными «событиями» для чернокожих писателей и художников этого города.

Регина Андерсон также организовывала мероприятия в публичной библиотеке Гарлема, где она работала помощником библиотекаря. Она читала новые книги увлекательных черных авторов, писала и распространяла дайджесты, чтобы пробудить интерес к ним.

Эти женщины были неотъемлемой частью Гарлемского Возрождения для многих ролей, которые они играли. Как организаторы, редакторы и лица, принимающие решения, они помогали популяризировать, поддерживать и тем самым формировать движение.

Но женщины также участвовали более непосредственно. В самом деле, Джесси Фосет многое сделала для облегчения работы других художников: она была литературным редактором «Кризиса», она организовывала салоны в своем доме и организовывала первую публикацию работ поэта Лэнгстона Хьюза. Но Фосе сама писала статьи и романы. Она не только сформировала движение извне, но и сама внесла в него художественный вклад.

В более широкий круг женщин в движении входили такие писатели, как Дороти Уэст и ее младшая кузина Джорджия Дуглас Джонсон, Халли Куинн и Зора Нил Херстон; такие журналисты, как Элис Данбар-Нельсон и Джеральдин Дисмонд; такие артисты, как Огаста Сэвидж и Лоис Майло Джонс; и такие певцы, как Флоренс Миллс, Мэриан Андерсон, Бесси Смит, Клара Смит, Этель Уотерс, Билли Холидей, Ида Кокс и Глэдис Бентли. Многие из этих художников обращались не только к расовым вопросам, но и к гендерным вопросам, а также исследовали, каково это жить чернокожей женщиной. Некоторые обращались к культурным вопросам «перехода» или выражали страх перед насилием или препятствиями на пути к полному участию в экономической и социальной жизни американского общества. Некоторые прославляли культуру чернокожих и работали над ее творческим развитием.

Почти забыты несколько белых женщин, которые также были частью Гарлемского Возрождения в качестве писателей, покровителей и сторонников. Мы знаем больше о черных мужчинах, таких как W.E.B. дю Буа и белых мужчин, таких как Карл Ван Вехтен, который поддерживал чернокожих женщин-художников того времени, чем о белых женщинах, которые были вовлечены. Среди них были богатая «леди-дракон» Шарлотта Осгуд Мейсон, писательница Нэнси Кунард и журналистка Грейс Халселл.

Marcus Garvey

Marcus Garvey

Few activists had the impact Marcus Garvey brought to the African American community in a short span of time — and all out of Harlem. The Jamaican-born leader took residence in Harlem and began a series of innovative projects and movements that focused on the Black working class. While Garvey was seen as a radical figure that advocated for the return to Africa of many dark-skinned African Americans, his motives were to install Black pride in a community oppressed by racism.

In 1914, Garvey founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), later making Liberty Hall in Harlem its headquarters. By the 1920s, the UNIA had over 700 chapters across America and Garvey commanded influence.

In August 1920, delegates from around the world packed the hall for a convention, and more than 25,000 people later marched from Harlem to Madison Square Garden, where Garvey held a rally.

Like many African American leaders at the time, Garvey became the target of the U.S. government and he was convicted and imprisoned for mail fraud in 1923. He was later pardoned by President Calvin Coolidge and deported back to Jamaica in 1927.

A tribute to his contribution forever stands in Harlem with Marcus Garvey Park, dedicated to nurturing the community he sought to improve.

Alice Dunbar Nelson

Alice Dunbar Nelson

Alice Dunbar Nelson was born to mixed-race parents in New Orleans, setting the tone for the nuanced take on race, gender and ethnicity she explored through her work.

A poet and activist, Dunbar Nelson’s first book, Violets and Other Tales (1985), was published when she was just 20 years old. A writer of many genres, Dunbar Nelson is most remembered for her prose. As one of the only female African American diarists of the era, she wrote about topics such as racism, sexuality and family.

She made her mark on the legacy of the Harlem Renaissance through her many reviews of writers like Hughes while living in the New York City neighborhood. Dunbar Nelson is also credited for helping establish the White Rose Mission in Harlem, a Christian, nonsectarian Home for Colored Girls and Women. The Mission also offered job placement for African Americans coming to the city in the post-Civil War migration.

Конец эпохи Возрождения

Депрессия сделала литературную и артистическую жизнь более сложной в целом, даже несмотря на то, что она нанесла больше экономического ущерба общинам чернокожих, чем общинам белых. Белым мужчинам отдавалось еще больше предпочтений, когда не хватало рабочих мест. Некоторые деятели Гарлемского Возрождения искали более высокооплачиваемую и безопасную работу. Америка стала меньше интересоваться афроамериканским искусством и художниками, рассказами и рассказчиками. К 1940-м годам многие творческие деятели Гарлемского Возрождения уже были забыты всеми, за исключением нескольких ученых, узко специализирующихся в этой области.

Bessie Smith

Bessie Smith

Bessie Smith became known as the “Empress of the Blues” thanks to her captivating and powerful vocals.

Smith was born in Chattanooga, Tennessee, and was working as a blues singer by the time she was 18. She soon joined the Rabbit Foot Minstrels and met the legendary Ma Rainey, who took Smith under her wing.

Smith eventually made her way to New York where her first release, “Down-Hearted Blues,” became a huge hit. She went on to record with legendary artists like Armstrong during her time in the Harlem scene.

While Smith’s popularity continued for some time, but toward the end of her life, she lost popularity. She died at 43 years old in 1937 from injuries sustained in a car accident.

The legacy of the Harlem Renaissance

The Harlem Renaissance was vibrant, but eventually it burned out. With the dawn of the Great Depression and the end of Prohibition, Harlem’s economic prosperity waned. By 1935, economic blight, housing and employment discrimination, and ongoing police brutality toward Black residents had created a tinderbox. That year, an erroneous rumor that police had beaten to death a Black teenager suspected of shoplifting sparked a race riot in Harlem. By World War II, the renaissance was a thing of the past.

Yet its influence lives on. The cultural upswell of the Harlem Renaissance set the stage for the modern flourishing of Black artists and thinkers and the continued struggle for civil rights for Black Americans. As historian Clement Alexander Price wrote, “The embittered past of Blacks was taken onto a much higher plane of intellectual and artistic consideration during the Harlem Renaissance….one of modern America’s truly significant artistic and cultural movements.”

Who Were the Women?

Most of the well-known figures of the Harlem Renaissance were men: W.E.B. DuBois, Countee Cullen, and Langston Hughes are names known to most serious students of American history and literature today. And, because many opportunities that had opened up for Black men had also opened up for women of all races, African American women too began to «dream in color»—to demand that their view of the human condition be part of the collective dream.

Jessie Fauset not only edited the literary section of «The Crisis,» but she also hosted evening gatherings for prominent Black intellectuals in Harlem: artists, thinkers, writers. Ethel Ray Nance and her roommate Regina Anderson also hosted gatherings in their home in New York City. Dorothy Peterson, a teacher, used her father’s Brooklyn home for literary salons. In Washington, D.C., Georgia Douglas Johnson’s «freewheeling jumbles» were Saturday night «happenings» for Black writers and artists in that city.

Regina Anderson also arranged for events at the Harlem public library where she served as an assistant librarian. She read new books by exciting Black authors and wrote up and distributed digests to spread interest in the works.

These women were integral parts of the Harlem Renaissance for the many roles they played. As organizers, editors, and decision-makers, they helped publicize, support, and thus shape the movement.

But women also participated more directly. Indeed Jessie Fauset did much to facilitate the work of other artists: She was the literary editor of «The Crisis,» she hosted salons in her home, and she arranged for the first publication of work by the poet Langston Hughes. But Fauset also wrote articles and novels herself. She not only shaped the movement from the outside, but was an artistic contributor to the movement herself.

The larger circle of women in the movement included writers like Dorothy West and her younger cousin, Georgia Douglas Johnson, Hallie Quinn, and Zora Neale Hurston; journalists like Alice Dunbar-Nelson and Geraldyn Dismond; artists like Augusta Savage and Lois Mailou Jones; and singers like Florence Mills, Marian Anderson, Bessie Smith, Clara Smith, Ethel Waters, Billie Holiday, Ida Cox, and Gladys Bentley. Many of these artists addressed not only race issues, but gender issues, as well—exploring what it was like to live as a Black woman. Some addressed cultural issues of «passing» or expressed the fear of violence or the barriers to full economic and social participation in American society. Some celebrated Black culture—and worked to creatively develop that culture.

Nearly forgotten are a few White women who also were part of the Harlem Renaissance, as writers, patrons, and supporters. We know more about the Black men like W.E.B. du Bois and White men like Carl Van Vechten, who supported Black women artists of the time, than about the White women who were involved. These included the wealthy «dragon lady» Charlotte Osgood Mason, writer Nancy Cunard, and Grace Halsell, journalist.

Aaron Douglas

Aaron Douglas

Aaron Douglas has long been called the “Father of African Art” thanks to his impactful paintings that were shaped by the pillars of the Harlem Renaissance.

Douglas made his way to New York City from his native Kansas in search of the hubbub of talent he had heard about. Once there, Douglas made famous friends in fellow leaders W.E.B. Du Bois, Alain Locke and James Weldon Johnson, all of whom featured his work in famous publications and even their own books.

The artist was known for his dramatic geometric shapes and flat forms that he used to tell the story of the Black experience.

Douglas eventually made his mark on Harlem permanent with a mural on the New York Public Library’s 135th location entitled Aspects of Negro Life. The breathtaking piece shows three facets of the Black experience: a figure symbolizing the escape from slavery, one showing the economic hardships of African Americans and the third holding a saxophone, paying tribute to the rich opportunities Black artists had thanks to the Renaissance.

A high sense of pride among the blacks fueled the Renaissance

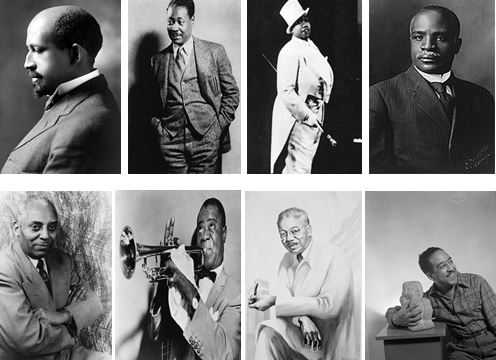

Harlem Renaissance Artist and scholars – from top left to right bottom – W.E.B. Du Bois (philosopher and civil rights activist), Claude McKay (Jamaican writer and poet), Gladys Bentley (Blues singer), Kelly Miller (mathematician), Noble Sissle (Jazz Composer), Louis Armstrong (Jazz trumpeter), Aaron Douglas (painter and illustrator), and Langston Hughes (poet and playwright)

A number of scholars and historians have opined that the pride and faith blacks kept in their own race played crucial role in sustaining the Harlem Renaissance. Obviously, increased literacy in the various black communities also helped. However, take away that sheer determination and pride, and the Harlem might have not lasted that long.

Taking pride in their works, African Americans began to communicate and interact in manner that enhanced them. Orchestrating this were organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Community leaders kept the movement alive by encouraging African Americans to appreciate their uniqueness in a predominantly White-dominated political and economic nation. This was perhaps the exact moment when Harlem Renaissance started to cross state lines and into overseas nations with black communities.

Read More:

- Frequently Asked Questions about Rosa Parks, the Mother of the Civil Rights Movement

- Major Accomplishments of Malcolm X

Luminaries of the Harlem Renaissance

The Harlem Renaissance unfolded across multiple modes of expression, from music to fashion, from poetry to philosophy. It was alive in blues and jazz music by figures like Bessie Smith, Cab Calloway, Dizzy Gillespie, and Billie Holiday. It could be found in poems by Langston Hughes and Georgia Douglas Johnson, novels by Zora Neale Hurston and Wallace Thurman, paintings by Aaron Douglas and Beauford Delaney, and the emergence of Black periodicals like The Crisis and Fire!!

The era’s Black tastemakers helped mentor, promote, and encourage the renaissance. The rise of mass communication allowed Black advocacy organizations like the NAACP a national voice. Jessie Redmon Fauset, the literary editor of the NAACP magazine The Crisis, used the platform to bring national attention to Black authors. She becameknown as the “midwife of the Harlem Renaissance.” Another Harlem Renaissance-era kingmaker was the writer Alain Locke, dubbed the movement’s “dean” for his mentorship of figures like Hughes and Hurston and his insistence that Black artists draw attention to, and inspiration from, their cultural heritage.

(Meet the historian who fought to make Black History Month possible.)

Activists like Marcus Garvey and W.E.B. DuBois encouraged a sense of Black excellence, pride, and shared identity widely known as the “New Negro” movement. Instead of yielding to the era’s relentless racism, the movement’s proponents openly protested it. They embraced ideals of education and progress and poured their energy into the struggle for civil rights through organizations like the NAACP, the Universal Negro Improvement Association, and African Communities League. These institutions encouraged Black Americans to agitate for social change and civil rights, including protesting the ongoing practice of lynching throughout the U.S.

Контекст

Это было в начале двадцатого века, и для нового поколения афроамериканцев мир сильно изменился по сравнению с миром их родителей, бабушек и дедушек. Система порабощения закончилась в Америке более полувека назад. Хотя афроамериканцы по-прежнему сталкивались с огромными экономическими и социальными препятствиями как в северных, так и в южных штатах, возможностей было больше, чем было.

После гражданской войны (и начавшейся несколько раньше на Севере) образование для чернокожих американцев — и черных и белых женщин — стало более распространенным. Многие по-прежнему не могли посещать или окончить школу, но некоторые из них могли посещать и окончить не только начальную или среднюю школу, но и колледж. В эти годы профессиональное образование постепенно стало открываться для чернокожих мужчин и женщин и белых женщин. Некоторые чернокожие стали профессионалами: врачи, юристы, учителя, бизнесмены. Некоторые темнокожие женщины также нашли профессиональную карьеру, часто в качестве учителей или библиотекарей. Эти семьи, в свою очередь, позаботились об образовании своих дочерей.

Когда черные солдаты вернулись в Соединенные Штаты после боев в Первой мировой войне, многие надеялись на открывшуюся возможность. Черные люди внесли свой вклад в победу; конечно, Америка теперь приветствовала бы этих людей в полноправном гражданстве.

В тот же период чернокожие американцы начали переезжать из сельских районов Юга в города и поселки промышленного Севера, в первые годы «Великой миграции». Они принесли с собой «черную культуру»: музыку с африканскими корнями и рассказывание историй. Общая культура США начала воспринимать элементы этой культуры черных как свои собственные. Это усыновление (и зачастую незасчитываемое присвоение) ясно проявилось в новом «веке джаза».

У многих афроамериканцев постепенно росла надежда, хотя дискриминация, предрассудки и закрытые двери по признаку расы и пола никоим образом не были устранены. В начале двадцатого века казалось более целесообразным и возможным бросить вызов этой несправедливости: возможно, несправедливости действительно можно было исправить или, по крайней мере, смягчить.

The Context

It was the early twentieth century, and for a new generation of African Americans, the world had changed tremendously compared to the world of their parents and grandparents. The system of enslavement had ended in America more than half a century earlier. While African Americans still faced tremendous economic and social obstacles in both the northern and southern states, there were more opportunities than there had been.

After the Civil War (and beginning slightly earlier in the North), education for Black Americans—and Black and White women—had become more common. Many were still not able to attend or complete school, but a substantial few were able to attend and complete not only elementary or secondary school, but college. In these years, professional education slowly began to open up to Black men and women and White women. Some Black men became professionals: physicians, lawyers, teachers, businessmen. Some Black women also found professional careers, often as teachers or librarians. These families, in turn, saw to the education of their daughters.

When Black soldiers returned to the United States from fighting in World War I, many hoped for an opening of opportunity. Black men had contributed to the victory; surely, America would now welcome these men into full citizenship.

In this same period, Black Americans began moving out of the rural South and into the cities and towns of the industrial North, in the first years of the «Great Migration.» They brought «Black culture» with them: music with African roots and story-telling. The general U.S. culture began adopting elements of that Black culture as its own. This adoption (and often-uncredited appropriation) was evidenced clearly in the new «Jazz Age.»

Hope was slowly rising for many African Americans—though discrimination, prejudice, and closed doors on account of race and sex were by no means eliminated. In the early twentieth century, it seemed more worthwhile and possible to challenge those injustices: Perhaps the injustices could indeed be undone, or at least eased.

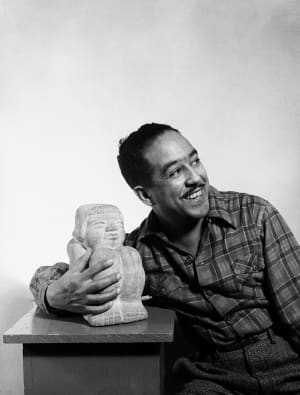

Langston Hughes

Langston Hughes

One of the leaders of the Renaissance, Langston Hughes made his mark by using his art to show the universal experience of the Black community.

According to critic Donald B. Gibson, Hughes “differed from most of his predecessors among black poets… in that he addressed his poetry to the people, specifically to Black people. During the twenties when most American poets were turning inward, writing obscure and esoteric poetry to an ever decreasing audience of readers, Hughes was turning outward, using language and themes, attitudes and ideas familiar to anyone who had the ability simply to read.”

Hughes died in 1967 of complications of prostate cancer at 65. To honor him, his Harlem residence was given landmark status by the New York City Preservation Commission and the street he lived on was renamed “Langston Hughes Place.”

How the Harlem Renaissance began

Harlem’s growth into a cultural center was spurred by the Great Migration—a decades-long exodus of Black Southerners to northern metropolises that began around 1915. Black people left the South for multiple reasons, including harsh Jim Crow laws that denied Black people their civil rights and economic conditions that made advancement next to impossible. They saw opportunity in northern cities, where workers were needed during labor shortages sparked by World War I. Between 1915 and about 1960, northern industrial cities absorbed five million Black people.

Many went to Harlem—a New York neighborhood that had once been a rural, wealthy white enclave. During a real estate crash at the turn of the 20th century, landlords became more willing to rent to Black tenants. Property values then plummeted as white residents attempted to offload their real estate and move away. Eventually, the area became majority Black, and Harlem turned into a magnet for migrants in search of economic opportunity and a rich cultural and social life.

These newcomers weren’t just from the American South: A substantial subset came from Caribbean countries like Jamaica, Antigua, and Trinidad, escaping economic downturns caused by the decline of sugar prices throughout the West Indies. By 1930, notes historian Jason Parker, a quarter of all Harlem residents hailed from the West Indies.

(See Black America’s story, told like never before.)

That cultural mixture spurred new types of expression and thought. Nurtured by Black churches and businesses, Harlem teemed with life. There, a poor Black worker could brush shoulders with educated, wealthy Black residents. They could take part in entertainment by Black people, for Black people. And they could be exposed to a vision of Black achievement and potential that was unheard of in most parts of the United States.

Criticism Of The Harlem Renaissance

Many people disapprove of Harlem Renaissance for struggling to create a new culture that separated them from the white culture. Harlem intellects resorted to mimicking whites by copying their clothing and manners to raise racial awareness and encourage assimilation. Critics argue that racial awareness could be attained without trying to look and act white. Due to its appeal to the mixed audience, leading magazines and newspapers employed Harlem Renaissance writers but most black Americans opposed this arrangement because they believed white publishers portrayed black writers as licentious. Some big Harlem joints went to extremes to provide the best black entertainment to solely white audiences.

Background Of The Harlem Renaissance

After the civil war, freed African-Americans longed for economic, cultural, civic, and political rights. Institutionalized racism was still rampant in the South and discrimination could be found country-wide. Due to hardships, most blacks started migrating north in large numbers. Many players in the Harlem Renaissance were part of the early 20th century migrants into the North and Midwest. Others were the black middle class and people of African descent from the Caribbean who came to the US in search of greener pastures. These groups converged in Harlem. The great migration brought many black Americans from Chicago, Philadelphia and Detroit. In Harlem, they still encountered racism, although not to the same extent as in the South.

Accomplishments Of The Harlem Renaissance

The Harlem Renaissance opened opportunities for black residents whose works were published and attracted nationwide attention. The Renaissance laid foundations for future black protest movements and movements. The renaissance enhanced racial consciousness through ethnic pride. Some African-Americans were lucky enough to get money, property, and obtain college degrees. The renaissance brought black skills into American history and culture. Harlem Renaissance encouraged the booming of blues music genre used by some artists to express themselves. It also led to the challenging of gender roles, sexuality, and sexism.

Sterling A. Brown

Sterling A. Brown (front left) and other African American poets

Poet Sterling A. Brown was welcomed into the Harlem Renaissance legacy after his first book Southern Road was published to critical acclaim.

Born in 1901 in Washington, D.C., Brown received a high-profile education at places like Williams College and Harvard University, later teaching at Howard University.

His work was influenced by African American music and his writings mused on race and class in America, like that of Hurston, Hughes and Cullen. Though the kept him from being published again for decades, Brown eventually released his second book, The Last Ride of Wild Bill, in 1975.