В опере

До Вагнера

Некоторые элементы оперы, ищущие более «классическую» формулу, появились в конце 18 века. После длительного доминирования Opera seria и da capo aria началось движение за продвижение либреттиста и композитора по отношению к певцам и за возвращение драмы к более интенсивной и менее моралистической направленности. Это движение, «опера реформ», в первую очередь ассоциируется с Кристофом Виллибальдом Глюком и Раньери де Кальцабиджи . Темы опер, созданных в сотрудничестве Глюка с Кальцабиджи, продолжаются в операх Карла Марии фон Вебера , пока Вагнер, отвергая итальянскую традицию бельканто и французскую «зрелищную оперу», не развил свой союз музыки, драмы, театральных эффектов. и иногда танцуют.

Однако эти тенденции возникли случайно, а не в ответ на определенную философию искусства; Вагнер, который признал реформы Глюка и восхищался работами Вебера, изначально хотел закрепить его взгляды как часть своих радикальных социальных и политических взглядов конца 1840-х годов. До Вагнера другие, которые выражали идеи о союзе искусств, что было знакомой темой среди немецких романтиков , о чем свидетельствует название эссе Трандорфа, в котором впервые появилось слово «Эстетика или теория философии искусства». . Среди других авторов синтезов искусств были Готтхольд Эфраим Лессинг , Людвиг Тик и Новалис . В восторженном обзоре Карла Марии фон Вебера оперу ЭТА Хоффмана « Ундина» (1816) она восхищалась как «произведение искусства, завершенное само по себе, в котором частичные вклады родственных и сотрудничающих искусств сливаются воедино, исчезают и, исчезнув, каким-то образом». сформировать новый мир ».

Идеи Вагнера

Вагнер использовал точный термин «Gesamtkunstwerk» (который он записал «Gesammtkunstwerk») только два раза, в своих эссе 1849 года « Искусство и революция » и « Произведение искусства будущего », где он говорит о своем идеале объединения всех произведений искусства. искусство через театр. Он также использовал в своих эссе много похожих выражений, таких как «непревзойденное произведение искусства будущего» и «интегрированная драма», и часто ссылался на «Gesamtkunst». Такое произведение искусства должно было стать самым ярким и глубоким выражением народной легенды.

Вагнер считал, что греческие трагедии Эсхила были лучшими (хотя все еще ошибочными) примерами полного художественного синтеза, но этот синтез впоследствии был искажен Еврипидом . Вагнер чувствовал, что на протяжении всей остальной истории человечества вплоть до наших дней (т.е. 1850 г.) искусства все дальше и дальше отдалялись друг от друга, что привело к появлению таких «чудовищ», как Гранд Опера . Вагнер считал, что такие произведения прославляют бравурное пение, сенсационные сценические эффекты и бессмысленные сюжеты. В «Искусстве и революции» Вагнер применяет термин «Gesamtkunstwerk» в контексте греческой трагедии. В «Произведении искусства будущего» он применяет его к своему собственному, пока еще не реализованному, идеалу.

В своей обширной книге « Опера и драма» (завершенной в 1851 году) Вагнер развивает эти идеи дальше, подробно описывая свою идею союза оперы и драмы (позже названной музыкальной драмой, несмотря на неодобрение этого термина Вагнером), в которой отдельные искусства подчинены общей цели.

Собственный оперный цикл Вагнера Der Ring des Nibelungen , в частности его компоненты Das Rheingold и Die Walküre , представляют, пожалуй, самое близкое, что он или кто-либо другой, подошел к реализации этих идеалов. После этого этапа Вагнер пришел к тому, чтобы ослабить свои ограничения и писать более условно, «оперативно».

Движение искусств и ремесел

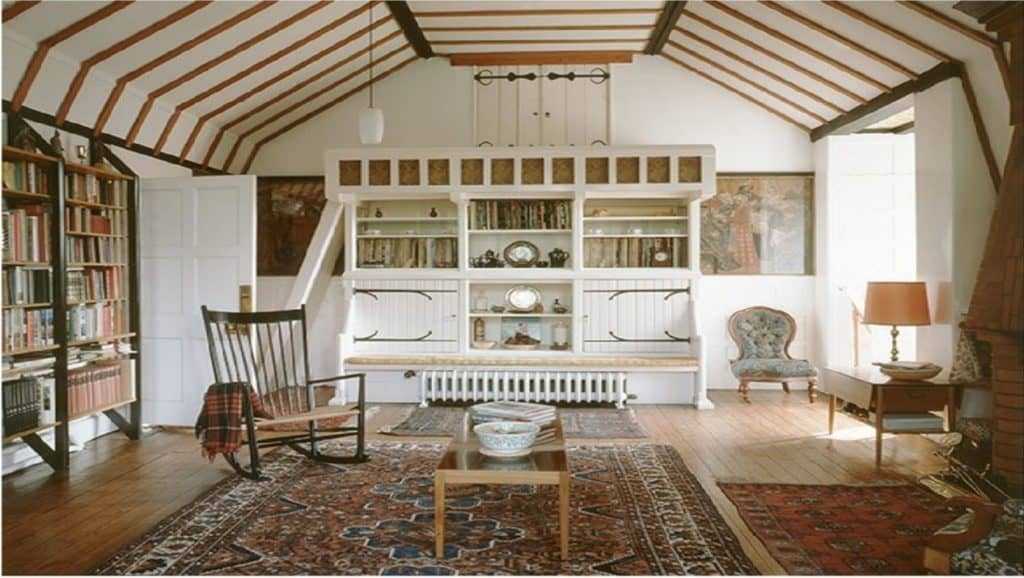

Уильям Моррис (1834–1896), британский текстильный дизайнер, поэт, писатель, переводчик и социалистический активист, был связан с британским движением искусств и ремесел , в значительной степени под влиянием идей Джона Раскина , который считал, что индустриализация привела к качественному упадок художественно созданных товаров. По его мнению, дом должен не только поддерживать гармонию, но и наполнять своих жителей творческой энергией.

«В ваших домах не должно быть ничего, что вы не считаете полезным или не считаете красивым» — это знаменитая цитата Уильяма Морриса, которая олицетворяет его собственный образ жизни из Gesamtkunstwerk.

Моррис и Филипп Уэбб «s Красный дом , разработанный в 1859 году, является одним из основных примеров, а также Blackwell Дом в английском Озерном крае , разработанный Бэйли Скотт . Blackwell House был построен в 1898–1900 годах как дом отдыха для сэра Эдварда Холта, богатого манчестерского пивовара. Он расположен недалеко от города Боунесс-он-Уиндермир. Из него открывается вид на Уиндермир и холмы Конистон.

Wagner’s ideas

Wagner used the exact term ‘Gesamtkunstwerk’ (which he spelt ‘Gesammtkunstwerk’) on only two occasions, in his 1849 essays «Art and Revolution» and «The Artwork of the Future», where he speaks of his ideal of unifying all works of art via the theatre. He also used in these essays many similar expressions such as ‘the consummate artwork of the future’ and ‘the integrated drama’, and frequently referred to ‘Gesamtkunst’. Such a work of art was to be the clearest and most profound expression of a folk legend, though abstracted from its nationalist particulars to a universal humanist fable.

Wagner felt that the Greek tragedies of Aeschylus had been the finest (though still flawed) examples so far of total artistic synthesis, but that this synthesis had subsequently been corrupted by Euripides. Wagner felt that during the rest of human history up to the present day (i.e. 1850) the arts had drifted further and further apart, resulting in such ‘monstrosities’ as Grand Opera. Wagner felt that such works celebrated bravura singing, sensational stage effects, and meaningless plots. In «Art and Revolution» Wagner applies the term ‘Gesamtkunstwerk’ in the context of Greek tragedy. In «The Art-Work of the Future» he uses it to apply to his own, as yet unrealised, ideal.

In his extensive book Opera and Drama (completed in 1851) he takes these ideas further, describing in detail his idea of the union of opera and drama (later called music drama despite Wagner’s disapproval of the term), in which the individual arts are subordinated to a common purpose.

Wagner’s own Ring cycle, and specifically its components Das Rheingold and Die Walküre represent perhaps the closest he, or anyone else, came to realising these ideals; he was himself after this stage to relax his own strictures and write more ‘operatically’.

Gesamtkunstwerk in architecture

The use of the term Gesamtkunstwerk in an architectural context signifies the fact that the architect is responsible for the design and/or overseeing of the building’s totality: shell, accessories, furnishings, and landscape. It is difficult to make a claim for when the notion of the Gesamtkunstwerk was first employed from the point of view of a building and its contents; already during the Renaissance, artists such as Michaelangelo saw no strict division in their tasks between architecture, interior design, sculpture, painting and even engineering. A later example occurs in the Baroque, for instance the work of the Austrian Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach, who was an architect and sculptor, as well as an architectural historian. «His buildings can be considered total works of art in which architecture and the figurative arts are united to express a predominant idea—the glorification of God or the patron saint in ecclesiastical architecture or the allegorical glorification of the ruler or of the noble patron in secular buildings… All of his works are composed of several different elements or contrasting features that are harmonized in a unified whole and in reference to their natural and artistic environment». The idea of Gesamtkunstwerk in architecture in the era following Romanticism is synonymous with the Art Nouveau; for example in the works of Josef Hoffmann and Otto Wagner in Austria, Henry van de Velde, Victor Horta and Paul Hankar in Belgium, Charles Rennie Mackintosh in Scotland, Antoni Gaudí in Spain and Eliel Saarinen in Finland. For example, Henry van de Velde built a house for his own family at Uccle near Brussels in 1895 in which he demonstrated the ultimate synthesis of all the arts, for apart from integrating the house with all its furnishings, including the cutlery, he even attempted to consummate the whole Gesamtkunstwerk through the flowing forms of the dresses that he designed for his wife. In another example, in the studio home of the architects Gesellius, Lindgren, and Saarinen, Hvitträsk (1902) in Finland the architects designed their own studio homes, the interiors, furniture, carpets, artworks and the exterior landscaping. It has been argued by historian Robert L. Delevoy that Art Nouveau represented an essentially decorative trend that thus leant itself to the idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk. But it was equally born from social theories born from a panic fear of the rise of industrialism—while at the same time determined to create a new style.

Frank Lloyd Wright: Interior of the Robie House, Chicago, 1909.

A distinctly modern approach to the concept of Gesamtkunstwerk emerged with the Bauhaus school, first established in Weimar in 1919 by Walter Gropius. The school specialised in design, art and craftsmanship (architecture was not introduced as a separate course until 1927 after it had transferred to Dessau). Gropius contended that that artists and architects should also be a craftsmen, that they should have experience working with different materials and artistic mediums, including industrial design, clothes design and theatre and music. However, Gropius did not necessarily see a building and every aspect of its design as being the work of a single hand. While certain architects have been known to be involved in other design aspects of design such as industrial design, painting and sculpture, it is rare for architects to concern themselves with a Gesamtkunstwerk approach. Exceptions are Frank Lloyd Wright (1867–1959) and Alvar Aalto (1898–1976).

Формирование концепции в архитектуре и художественных ремёслах

Теорию единого происхождения всех видов «изящных», а также бифункциональных (прикладных) видов искусства и художественных ремесел на основе формообразующих принципов архитектуры разрабатывал в середине XIX в. немецкий архитектор Готфрид Земпер (b) . В 1843 г. из Парижа в Дрезден приехал композитор Р. Вагнер для постановки в местном театре, возведенном по проекту Г. Земпера, оперы «Летучий голландец». Земпера и Вагнера сблизили общие идеи, мечты о преодолении раздробленности видов искусства и создании «большого стиля». Вагнер мечтал о единстве драмы, поэзии и музыки, как это было у древних греков. Земпер искал общие закономерности формообразования в архитектуре, орнаменте и художественных ремеслах. По мнению обоих, такой синтез уже существовал однажды, в античности, он возможен и в искусстве будущего, когда музыка, драма, танец, архитектура и изобразительное искусство снова сольются в единое ремесло и «перестанут быть праздной забавой в руках скучающих бездельников». Однако в мае 1848 г. в Германии разразилась революция, художники оказались на баррикадах, а после подавления восстания вынуждены были эмигрировать. Вагнер бежал в Швейцарию, Земпер уехал во Францию, собирался перебраться в Северную Америку, но получил приглашение приехать в Лондон для участия в подготовке экспозиции первой Всемирной выставки 1851 г. (b)

Г. Земпер, как и другие прогрессивно мыслящие художники, был удручен несоответствием функции, формы и декора многих изделий промышленного производства. Новые «машинные» формы декорировали не соответствующим их конструкции «готическим» или «рокайльным» орнаментом. После проведения выставки Земпер опубликовал книгу под названием «Наука, промышленность и искусство» с подзаголовком «Предложения по улучшению вкуса народа и в промышленности в связи с Всемирной промышленной выставкой в Лондоне в 1851 году». С 1855 г. Земпер жил и работал в Швейцарии, создавал свой основной (оставшийся незавершенным) труд «Стиль в технических и тектонических искусствах», или «Практическая эстетика» (нем. «Praktische Aesthetik»). Основная идея этого труда заключалась в разработке «практической теории», позволяющей преодолеть пагубное разделение искусства на «высокие» и «низкие» жанры, идеалистические устремления и материальную сторону творчества, проектирование (утилитарное формообразование) и последующее украшение изделий. Земпера занимал вопрос о месте технических форм в общем развитии культуры. Этот вопрос он пытался разрешить, обратившись к истории классического искусства и выявляя закономерности связи функции и формы изделий в различных условиях. В статьях и лекциях лондонского периода («Набросок системы сравнительной теории стилей», «Об отношении декоративного искусства к архитектуре») Земпер доказывал необходимость применения новой методологии. Вместо господствовавшей в то время академической теории о происхождении трех видов «изящных искусств» (итал. belli arti, франц. beaux arts), живописи, ваяния и зодчества, из искусства рисунка, «как это было у древних», немецкий архитектор и теоретик смело предположил первенство ремесел и технологии обработки материалов. Поэтому Земпера справедливо считают не только одним из создателей «гезамткунстверка», но и «отцом дизайна».

Идеологию единения искусств развивали представители школы Баухаус (b) (1919—1933). Ее директор Вальтер Гропиус (b) утверждал, что наполнение интерьера предметами обстановки должно поддерживать общую архитектурную концепцию. Текстиль, мебель и осветительные приборы должны подчиняться единой художественной идее.

In art[edit]

Hanover Merzbau, a mixed media installation by Dadaist Kurt Schwitters in his apartment, Hanover, 1933

The multi-media style pioneered by Dadaists such as Hugo Ball has also been called a Gesamtkunstwerk. ‘Towards the Merz Gesamtkunstwerk’ was a University of Oregon graduate seminar that explored themes of Dadaism and Gesamtkunstwerk, especially Kurt Schwitter’s legendary Merzbau. They cite Richard Huelsenbeck in his German Dada Manifesto: «Life appears as a simultaneous confusion of noises, colours and spiritual rhythms, and is thus incorporated — with all the sensational screams and feverish excitements of its audacious everyday psyche and the entirety of its brutal reality — unwaveringly into Dadaist art».

In 2011, Saatchi Gallery in London held Gesamtkunstwerk: New Art from Germany, a survey exhibition of 24 contemporary German artists.

An exhibition entitled Utopia Gesamtkunstwerk, curated by Bettina Steinbrügge and Harald Krejci, took place from January to May 2012 at the 21er Haus in Belvedere, Vienna. «A contemporary perspective of the historical idea of the total work of art» was presented and included a «display» by Esther Stocker which was based on the idea of «the untidy nursery», it housed works by Joseph Beuys, Monica Bonvicini, Christian Boltanski, Marcel Broodthaers, Daniel Buren, Heinz Emigholz, Valie Export, Claire Fontaine, gelatin, Isa Genzken, Liam Gillick, Thomas Hirschhorn, Ilya Kabakov, Martin Kippenberger, Gordon Matta-Clark, Paul McCarthy, Superflex, Franz West, and numerous others. There was an accompanying book produced with the same name exploring the topic.

Many reviews have characterized the contemporary art exhibition the 9th Berlin Biennale as a gesamtkunstwerk.

In 2017, prominent visual artists Shirin Neshat and William Kentridge directed operas at the Salzburg Festival.

Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Willow Tea Rooms

Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Willow Tea Rooms, Glasgow, 1903

The Willow Tea Rooms were established in Glasgow in 1903, designed by Charles Rennie Mackintosh. Mackintosh was a Scottish architect, designer and artist and tagged as “the design dictator” as a result of his desire to always mastermind the entirety of a project. To begin Mackintosh remodelled an 1860s edifice; the exterior façade was modernized, delving into early Art Nouveau ideas. Mackintosh worked with his wife, Margaret Macdonald, to design the interiors. This included the furniture, wall decorations and friezes, as well as the carpets and chandeliers; paying crucial attention to the smallest details such as creating bespoke cutlery and fashioning the staff’s uniforms, resulting in one of the most uncompromising of all Gesamtkunstwerk projects of the early modern, or any, era.

William Morris & Philip Webb, The Red House

William Morris & Philip Webb, The Red House, 1859

Reminiscent of a medieval relic, the Red House was designed in 1859 by Arts and Crafts designer William Morris and architect Philip Webb, in Bexleyheath, England. William Morris was greatly influenced by John Ruskin’s reflections, who believed that the rise of industrialisation induced a qualitative decline in artistically crafted goods. He endeavoured to fashion a home that would nurture harmony as well as infuse its inhabitants with a creative energy. Morris and Webb’s friendship led them to create a house in which architecture and interior design would blend into a cohesive entity, reflecting their ideals in one overarching whole. The house was designed in a simple Tudor Gothic style, and from the unique built-in furniture to the wallpaper, stained-glass windows, and tiles inscribed with Morris’s own motto, the concept of the total work of art was dazzlingly embodied.

The Red House, Drawing Room, 1859

Литература

- Bergande W. The creative destruction of the total work of art. From Hegel to Wagner and beyond // The death and life of the total work of art. Berlin: Jovis, 2014.

- Finger A.; Follett D. The Aesthetics of the Total Artwork: On Borders and Fragments. Baltimor: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011.

- Finger A. Das Gesamtkunstwerk der Moderne. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck&Ruprecht 2006.

- Fornoff R. Die Sehnsucht nach dem Gesamtkunstwerk. Studien zu einer ästhetischen Konzeption der Moderne. Hildesheim, Zürich, New York: Olms 2004.

- Schneller D. Richard Wagners «Parsifal» und die Erneuerung des Mysteriendramas in Bayreuth. Die Vision des Gesamtkunstwerks als Universalkultur der Zukunft. Bern: Lang 1997.

- Szeemann H. Der Hang zum Gesamtkunstwerk. Europäische Utopien seit 1800. Ausstellungs-Katalog. Zürich: Kunsthaus, 1983.

- Trahndorff K. F. Ästhetik oder Lehre von Weltanschauung und Kunst (1827). Nabu Press, 2011. — 712 p.

- Wolfman U. Richard Wagner’s Concept of the ‘Gesamtkunstwerk’ // Interlude, 2013.

- Радугин А. М. Синтез искусств // Эстетика. — Москва: Библионика, 2006. — С. 268—271

- Синтез искусств/ К. А. Макаров//Большая советская энциклопедия: / гл. ред. А. М. Прохоров (b) .— 3-е изд.— М.: Советская энциклопедия, 1969—1978.

References

- Millington (n.d.), Warrack (n.d.)

- Oxford English Dictionary, Gesamtkunstwerk

- Millington (n.d.)

- Wagner (1993), p.35, where the word is translated as ‘great united work’; p.52 where it is translated as ‘great unitarian Art-work’; and p.88 (twice) where it is translated as ‘great united Art-work’.

- Warrack (n.d.), Gesamtkunstwerk is incorrect in saying that Wagner used the word only in «The Artwork of the Future»

- Millington (n.d.)

- Grey (2008) 86

- Millington (1992) 294–5

- Michael A. Vidalis, «Gesamtkunstwerk — ‘total work of art'», Architectural Review, June 30, 2010.

- The New Encyclopaedia Brittanica, 15th edition.

- Robert L. Delevoy, ‘Art Nouveau’, in Encyclopaedia of Modern Architecture. Thames & Hudson, 1977.

- Arnold Wittick, Encyclopaedia of Modern Architecture. Thames & Hudson, 1977.

Before Wagner

Some elements of opera reform, seeking a more ‘classical’ formula, had begun at the end of the 18th century. After the lengthy domination of opera seria, and the da capo aria, a movement began to advance the librettist and the composer in relation to the singers, and to return the drama to a more intense and less moralistic focus. This movement, «reform opera» is primarily associated with Christoph Willibald Gluck and Ranieri de’ Calzabigi. The themes in the operas produced by Gluck’s collaborations with Calzabigi continue throughout the operas of Carl Maria von Weber, until Wagner, rejecting both the Italian bel canto tradition and the French «spectacle opera», developed his union of music, drama, theatrical effects, and occasionally dance.

However these trends had developed fortuitously, rather than in response to a specific philosophy of art; Wagner, who recognised the reforms of Gluck and admired the works of Weber, wished to consolidate his view, originally, as part of his radical social and political views of the late 1840s. Previous to Wagner, others who had expressed ideas about union of the arts, which was a familiar topic among German Romantics, as evidenced by the title of Trahndorff’s essay, in which the word first occurred, «Aesthetics, or Theory of Philosophy of Art». Others who wrote on syntheses of the arts included Gottfried Lessing, Ludwig Tieck and Novalis.

Bibliography[edit]

- Finger, Anke and Danielle Follett (eds.) (2011) The Aesthetics of the Total Artwork: On Borders and Fragments, The Johns Hopkins University Press

- Grey, Thomas S. (ed.) (2008) The Cambridge Companion to Wagner, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64439-6

- Koss, Juliet (2010) Modernism After Wagner, University of Minnesota Press, ISBN 978-0-8166-5159-7

- Krejci, Harald, Agnes Arco, and Bettina Steinbrügge. Utopia Gesamtkunstwerk. Köln: Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König, 2012. ISBN

- Millington, Barry (ed.) (1992) The Wagner Compendium: A Guide to Wagner’s Life and Music. Thames and Hudson Ltd., London. ISBN 0-02-871359-1

- Millington, Barry (n.d.) «Gesamtkunstwerk», in Oxford Music Online (subscription only) (consulted 15 September 2010)

- Trahndorff, Karl Friedrich Eusebius (1827) Ästhetik oder Lehre von Weltanschauung und Kunst

- Wagner, Richard (1993), tr. W. Ashton Ellis The Art-Work of the Future and Other Works. Lincoln and London, ISBN 0-8032-9752-1

- Warrack, John (n.d.) «Gesamtkunstwerk» in The Oxford Companion to Music online, (subscription only) (consulted 15 September 2019)

In opera[edit]

Before Wagneredit

Some elements of opera, seeking a more «classical» formula, had begun at the end of the 18th century. After the lengthy domination of opera seria, and the da capo aria, a movement began to advance the librettist and the composer in relation to the singers, and to return the drama to a more intense and less moralistic focus. This movement, «reform opera» is primarily associated with Christoph Willibald Gluck and Ranieri de’ Calzabigi. The themes in the operas produced by Gluck’s collaborations with Calzabigi continue throughout the operas of Carl Maria von Weber, until Wagner, rejecting both the Italian bel canto tradition and the French «spectacle opera», developed his union of music, drama, theatrical effects, and occasionally dance.[citation needed]

However these trends had developed fortuitously, rather than in response to a specific philosophy of art; Wagner, who recognised the reforms of Gluck and admired the works of Weber, wished to consolidate his view, originally, as part of his radical social and political views of the late 1840s. Previous to Wagner, others who had expressed ideas about union of the arts, which was a familiar topic among German Romantics, as evidenced by the title of Trahndorff’s essay, in which the word first occurred, «Aesthetics, or Theory of Philosophy of Art». Others who wrote on syntheses of the arts included Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Ludwig Tieck and Novalis.Carl Maria von Weber’s enthusiastic review of E.T.A. Hoffmann’s opera Undine (1816) admired it as ‘an art work complete in itself, in which partial contributions of the related and collaborating arts blend together, disappear, and, in disappearing, somehow form a new world’.

Wagner’s ideasedit

Wagner used the exact term ‘Gesamtkunstwerk’ (which he spelt ‘Gesammtkunstwerk’) on only two occasions, in his 1849 essays «Art and Revolution» and «The Artwork of the Future», where he speaks of his ideal of unifying all works of art via the theatre. He also used in these essays many similar expressions such as ‘the consummate artwork of the future’ and ‘the integrated drama’, and frequently referred to ‘Gesamtkunst’. Such a work of art was to be the clearest and most profound expression of folk legend.[citation needed]

Wagner felt that the Greek tragedies of Aeschylus had been the finest (though still flawed) examples so far of total artistic synthesis, but that this synthesis had subsequently been corrupted by Euripides. Wagner felt that during the rest of human history up to the present day (i.e. 1850) the arts had drifted further and further apart, resulting in such «monstrosities» as Grand Opera. Wagner felt that such works celebrated bravura singing, sensational stage effects, and meaningless plots. In «Art and Revolution», Wagner applies the term ‘Gesamtkunstwerk’ in the context of Greek tragedy. In «The Art-Work of the Future», he uses it to apply to his own, as yet unrealized, ideal.[citation needed]

In his extensive book Opera and Drama (completed in 1851), Wagner takes these ideas further, describing in detail his idea of the union of opera and drama (later called music drama despite Wagner’s disapproval of the term), in which the individual arts are subordinated to a common purpose.[citation needed]

Wagner’s own opera cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen, specifically its components Das Rheingold and Die Walküre, represent perhaps the closest he, or anyone else, came to realizing these ideals. After this stage, Wagner came to relax his own strictures and write more conventionally ‘operatically’.

Arts and Crafts movementedit

William Morris (1834–1896), a British textile designer, poet, novelist, translator, and socialist activist, was associated with the British Arts and Crafts movement, largely influenced by the ideas of John Ruskin, who believed that industrialization led to a qualitative decline in artistically crafted goods. For him, a home must nurture harmony as well as infuse its inhabitants with a creative energy.

«Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful» is the famous quote of William Morris that epitomized his own way of living of Gesamtkunstwerk.

Morris’ and Philip Webb’s Red House, designed in 1859, is a major example, as well as the Blackwell House in the English Lake District, designed by Baillie Scott. Blackwell House was built in 1898–1900, as a holiday home for Sir Edward Holt, a wealthy Manchester brewer. It is situated near the town of Bowness-on-Windermere with views looking over Windermere and across to the Coniston Fells.[citation needed]

Внешние ссылки [ править ]

- Словарное определение Gesamtkunstwerk в Викисловаре

- Навстречу Merz Gesamtkunstwerk — веб-сайт семинара для выпускников Университета Орегона

| vте Термины Opera по происхождению | |

|---|---|

| английский |

|

| Французский |

|

| Немецкий |

|

| Итальянский |

|

| Другой |

| vтеРомантизм | |

|---|---|

| Страны |

|

| Движения |

|

| Писатели |

|

| Музыка |

|

| Богословы и философы |

|

| Визуальные художники |

|

| похожие темы |

|

|

« Век Просвещения Реализм » |

| Авторитетный контроль |

|---|

![Gesamtkunstwerkсодержание а также фон [ править ]](http://thelawofattraction.ru/wp-content/uploads/b/7/1/b710e8d4ac84fe2cd123c4f90c1df626.png)